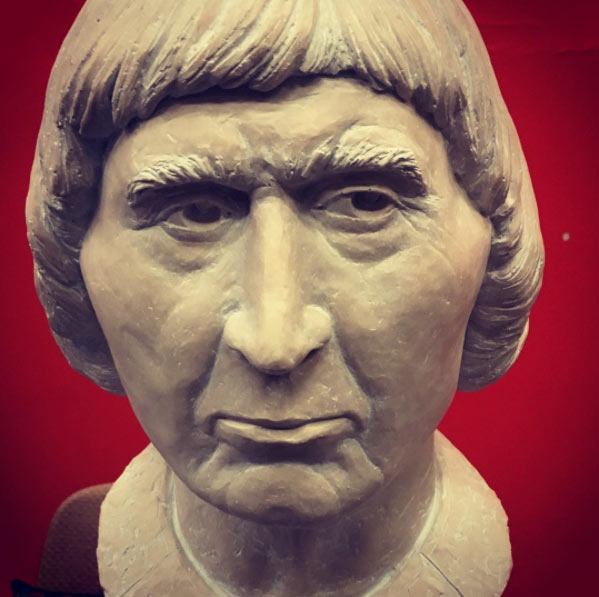

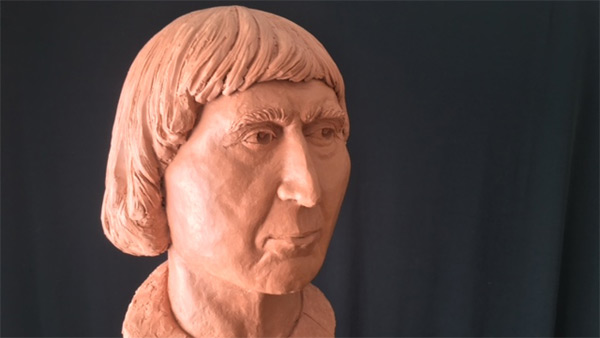

People may think … ‘not another facial reconstruction’ and just give this a fleeting glance, comment on the ‘funny’ hairstyle and not look any further. But this is so much more. Not only is this a scientifically based reconstruction based on facts rather than presumptions it gives us a new insight into the life of Robert the Bruce through the eyes of a world renowned portrait artist. This was a project started through the relationship between an artist and his sitter instigated by Christopher Robert Bruce (one of our admins on the Scottish Clans and Families Facebook group).

Artist Christian Corbet and The Earl of Elgin – How it started

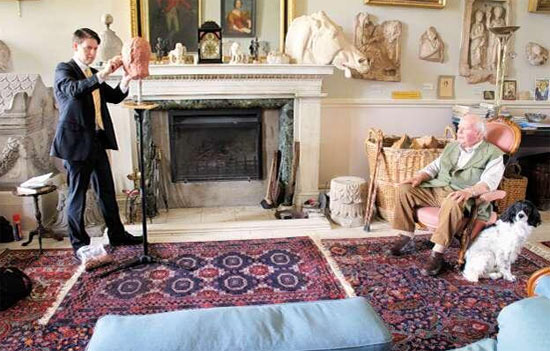

The Canadian artist Christian Corbet was commissioned to produce a portrait of The Earl of Elgin, chief of the Family of Bruce. Corbet has painted the Queen Mother, sculpted Prince Philip, he can boast an impressive list of portraits, both paintings and sculptures. A great artist does more than just photocopy an image they show an essence, a spark. A relationship between artist and their sitter gets added into the mix, though many hours of studies, conversations, research the art work evolves.

Discussion between The Earl of Elgin and Corbet naturally led to Robert the Bruce. Corbet became fascinated with the mythology surrounding Robert the Bruce. Could he create a portrait, a reconstruction of The Hero Scottish King? With Scottish ancestry this idea really appealed to Corbet, but how would it be possible to show an essence, tell the story, of someone who is surrounded in so much mystery?

With advice from the Earl of Elgin the aim was to produce a face uncovered, to show the man. To do this is not like creating a portrait of a living person, not even like creating a portrait of someone no longer with us where photography existed to refer to and help from living relatives. This was going to be a project like no other. Separating the King from the man, legends from facts and also dealing with what people expect. I’ve dressed my son as Robert the Bruce before to go Guising (Scottish halloween tradition). He was dressed in armour, crown and beard with a wooden hobby horse – this is what Robert the Bruce to me was. People recognised my son as Robert the Bruce, so know I’m not alone.

This was a project that needed expertise from many different specialists. The bio-archaeologist Dr Andrew Nelson from the University of Western Ontario joined the project also a renowned paleo-pathologist and leprosy expert from France and a professor specialising in forensic density, among others. Also Bruce historians, Christopher Robert Bruce played a large part in this. This reconstruction took three years of hard work.

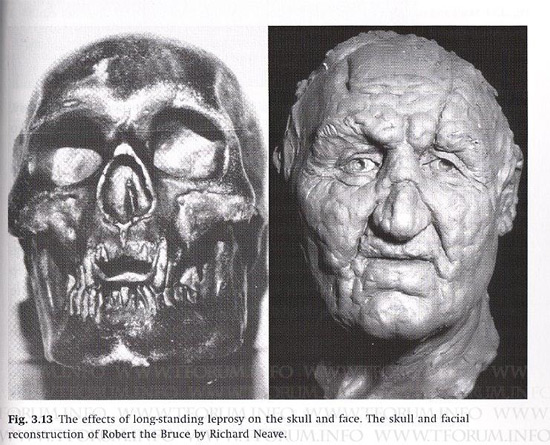

No evidence of Leprosy

The conclusion from all these specialists was the skull was not representative of an individual with leprosy. Looking at historical reasons Robert the Bruce could have been labelled a leper point to it being a slur after the battle of Bannockburn. The stigma attached to the disease makes him less of a man. This 700 year rumour/propaganda needs to be laid to rest.

So why the funny hair?

Quite simply the pageboy haircut was the style of the time. It would have been practical, the term ‘Helmet Hair’ comes from this.

Gary Stewart from the Society of William Wallace advised on the styles and fashions of the time Bruce lived in. Images of coins from the lifetime of Robert the Bruce were also sent to Corbet where the ‘page boy’ hairstyle can be seen .

The Plinth

Duncan Thomson from the Strathleven Artisans organised the plinth that the head was to stand on, it was made from wood taken from the historic Bruce Oak tree in Loch Lomond National Park.

Attending the Unveiling

I was privileged to attend the unveiling ceremony at the Stirling Smith Museum on March 23rd 2017. I have to be honest here I know basic history about Robert the Bruce, how he became King, the battles, like most other people under the assumption that he did have leprosy.

Sadly the artist Christian Corbet was unable to attend due to illness. Lord Charles Bruce gave a very thought provoking speech. My frantic note taking didn’t do it justice when I tried to write up my notes so I thought it would be best to keep to his actual notes which I am very thankful to have been given a copy of. I have just added some images.

Speech given by Lord Charles Bruce

“Few Scottish kings have held such a fascination for the portrait artist as Robert the Bruce – and yet we have no idea what he really looked like. He speaks to us from the pages of history predominantly as a warrior. Indeed most of his life was affected by war, a period equivalent to the First and Second World Wars fought back to back three times over. But behind the façade of a battle hardened soldier there lies the complexity of a man whose life was defined by contradiction. Although decisive and sometimes ruthless in battle he was also deeply pious. He may have laid waste to Buchan but he also erected shrines and chapels all over Scotland to honour his faith. He could be paralysed by self-doubt – remember the scene in the cave on Rathlin Island – but he also composed one of the most visionary and startling treatises on national identity ever written in the medieval period – the Declaration of Arbroath. He fought one of the bloodiest battles on British soil, Bannockburn, but wept openly over the body of the commander of his enemy’s forces, the Earl of Gloucester – who happened to be his brother in law.

At Stirling you have two versions of the King – one carved from sandstone by Andrew Currie and unveiled on the castle esplanade in 1877; and the other unveiled by the Queen at the Bannockburn Rotunda in 1964. The sculptor – Charles Pilkington-Jackson – clearly thought the equestrian king should be larger than life. He used three tonnes of clay to form the model but couldn’t find a foundry in Scotland big enough to forge the bronze.

In the last seven years alone my son Benedict and I have been asked to unveil two new versions of the King. At Annan in 2010, and the following year outside Marischall College in Aberdeen. Both figures show the king helmeted for battle and suited from head to toe in chain mail. One clutches a sword – the other holds aloft a charter granting the Forest of Stocken to the Burgers of Aberdeen.

It appears that the challenge to fit a face to a king who died nearly 700 years ago still continues to captivate us. Ever since King Robert’s body was discovered in Dunfermline Abbey in 1818, and a plaster model was cast from his skull, each succeeding generation has grafted his likeness onto the public imagination.

In recent times at least five attempts have been made to form a forensic reconstruction of the King’s face. But to my knowledge no artist has actually attempted to sculpt Robert the Bruce as an ordinary man of his time, stripped of the entablature of kingship, or the status of hero. Indeed it is this essential sense of intimacy that seems to have eluded sculptors and forensic scientists, until now.

Forensic reconstruction has an important role to play, but we also need the imagination of a gifted artist to place a medieval king securely on a 21st century plinth. We want to know more about the subject and to explore the psychology of medieval leadership. We want to be able to navigate the space within, in order to read the mind behind the face. I think you will agree that Christian Corbet has achieved this task. Not only has he captured the identity of one of our greatest heroes, but he has also allowed us to get much closer to Robert Bruce than I suggest that any of us had ever imagined would be possible.

It is unfortunate that Christian is unable to be with us today. But it is more than a coincidence perhaps that this gift to the Stirling Smith Museum and Gallery should have come from Canada. It was Eric Harvie, a Canadian businessman from Alberta whose generosity allowed the Pilkington- Jackson statue to be erected at Bannockburn in 1964, and another to be put up in his hometown of Calgary. Indeed the Bruce equestrian statue on the junction of 10th Avenue and 14th Street is a notable local landmark and encourages Calagarians to boast to credulous tourists that the Calgary Stampede is the only rodeo in North America with medieval origins.

Some of you will know that my father was actively involved in fundraising for the Pilkington Jackson commission and was actually responsible for securing the donation from Eric Harvie. But the land on which the statue was erected – forming part of the battlefield of Bannockburn – was secured for the nation by my grandfather in 1931. Alerted by news that Stirling Burgh Council had acquired the battlefield by compulsory purchase in order to build a council housing scheme, my grandfather organised a national appeal on behalf of the embryonic National Trust for Scotland to buy the land, and enlisted the help of John Buchan. Buchan was in the midst of writing the “Four Adventures of Richard Hannay” but he laid aside his pen to save the battlefield. He provided a foreword to the Appeal: “Bannockburn is a key-event in history”, he wrote. “For Scotland it is the proudest military event in her records. It gave her freedom. It created a national self-consciousness…it enabled her to find her soul. It left her…to work out her own destiny, and when union with her old antagonist came about, she entered as an equal, free and unconquered. Had its issue been otherwise, the whole history of Britain would have been different”.

There is no doubt that Buchan’s intervention was well received. The Appeal was successful and it had the twin effect of saving the battlefield and launching the National Trust for Scotland. But there is still a sense today that the whole exercise was slightly unseemly – that so much effort was required to overturn such a misconceived municipal decision. Indeed it was this type of collective amnesia and betrayal of history that so discouraged Thomas Carlyle, a century earlier, and prompted him to write that “we on the whole do our Hero-worship worse than any other Nation in this world ever did it before”. Of course Carlyle later reconsidered his criticism inspiring the creation of two portrait galleries in London and Edinburgh.

Opened in 1889 the SNPG was decorated shamelessly with a life-sized frieze painted in fresco by William Hole depicting no fewer than 150 figures from Scottish history arraigned in an imaginary procession. In the same year that the gallery opened my great grandfather commissioned a brass effigy of Robert the Bruce to be placed over the King’s tomb in Dunfermline Abbey.

The effigy is embedded in a slab of porphyry, a dense blood-coloured marble. The marble came into the possession of my family in 1801 as a gift from the Sultan of Turkey. It was reputed to have once formed the lid of the sarcophagus of the emperor Constantine but had long since been detached from the place of burial and was being used as a step to reach the front door of the Ottoman treasury in the Topkapi Palace. Leaving aside the controversy of the provenance of antiquities, it is perhaps with a sense of poetic justice that King Robert’s body should be buried under a funerary monument originally destined for one of the great princes of Christendom.

The story of King Robert’s death, burial, disinterment and reburial is an extraordinary tale of loss and rediscovery that reflects Carlyle’s criticism of his countrymen. The exhumation of the King’s body in February 1818 among the ruins of Dunfermline Abbey occurred only a few weeks after the discovery of the Scottish Regalia – the Honours of Scotland – in a cupboard in Edinburgh Castle. Although both discoveries were a cause of much jubilation, we cannot avoid the suspicion that the disappearance of such an important part of the nation’s heritage was a result of amnesia and inertia. The Regalia had been “put away” in 1707 after the sceptre was used for the last time to authorise the Act of Union – and thereafter all trace had been lost. The king’s body was discovered by workmen clearing rubble to allow a survey to be carried out for building a new abbey church. There was no sign of the elaborate marble tomb which King Robert had procured from France in 1315. That had long since disappeared in the Reformation. But even if it had survived the iconoclasts and Oliver Cromwell it would have been destroyed by falling masonry as the Abbey Choir collapsed for want of maintenance on four occasions between 1560 and 1808.

To fast-forward to the present day, a few years ago Christian was commissioned to sculpt a portrait head of my father. As you can well imagine during the lengthy sittings, artist and subject whiled away the time discussing Scottish history – and inevitably the part played by the Bruce family – with the result that Christian became fixated by the mythology surrounding the disinterment of King Robert. My father was able to lend him the family’s copy of the king’s skull, taken from William Scoular’s original mould. I understand that it didn’t take Christian long to decide that he would undertake a portrait head as an exemplary work of forensic science but also as a work of art. He would capture the king as a “lion in winter” in the year of his death in 1329 at the age of 55.

In tackling this challenging commission Christian has entirely reassessed the cause of the King’s death based on a profound re-evaluation of forensic evidence. Before I turn you over to Christian and his colleague Dr Andrew Nelson to allow them to explain how they have altered the way in which we visualise King Robert, there is a little more scene-setting to establish. You need to remember that in 1324 the King is thought to have acquired 200 acres of land by way of excambion with the Earl of Lennox, at Pelanyspflait in the Vale of Leven near to the present-day village of Renton in West Dumbartonshire. It was here that he built a comfortable oak-framed house with a well-stocked demesne, orchards and physic garden. Research carried out by the Strathleven Artizans has established without doubt the location of this dwelling. In order to understand what the artist has intended you have to imagine him in this context.

One of the founders of the Strathleven Artizans, Stuart Smith describes how the king lived out his final years:

“You builded your Manor, with roof of thatch And graced its shutters with Flemish Glass, Then grew potted herbs within a fence And scythed and hacked the briar wood dense To plant a King’s park and seed a Queens lawn, For you and your kinsmen to hunt till dawn.

You builded your Manor with plaster walls And raised up a Chapel with choir stalls And latticed its niches with Augsburg glass, In honour of someone’s burial Mass!

You builded your Manor with highland beams To house the roar of banquet scenes. In the park at Mains with fifteen fields You strode with the hounds that stayed to heel.

And when you went hawking in the Murroch Bog To the glimmer of dawn and the barking of dogs, Or when hunting tusk in the glen at Dalmoak ,The banquet to follow was a boars-head feast.

A tamed lion you kept, as a pet no less On a long silver chain, to greet every guest – As a reminder to all, that a lion with teeth, Guards the Kings Manor, as part of its brief!

There strode your foot upon this land: Feet that trod by the river leven side – Toes that scabbed at the shrinking tide. There lay a head on a great carved bed There lay a face which whispered dread! There lay a head with golden crown, There lay a king in his burial gown.”

—————————————————————————–

Further Information

More information about the project: http://christiancorbet.com/ http://mediarelations.uwo.ca/2017/02/16/western-researcher-forensic-sculptor-reject-scottish-king-roberts-leprosy-label/

19th Century Report on the skull of Robert the Bruce: https://archive.org/details/reporttorighthon00scot

I always enjoy Roger’s historical presentations….so very well done: not only educational but inspirational to all!

Thanks for the wonderful shares!