The Royal burgh of Forfar, a small faming and market town nestled in the Strathmore valley in Angus in the east of Scotland, is a respectable and quiet community. The burgh lies only five miles from Glamis Castle, family seat of the Earls of Strathmore and Kinghorn, childhood home of Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, and the setting for Shakespeare’s play Macbeth.

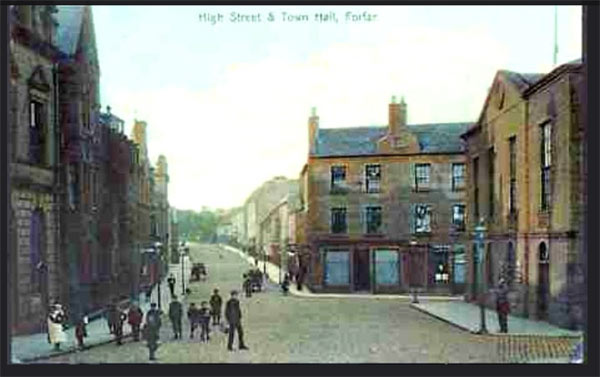

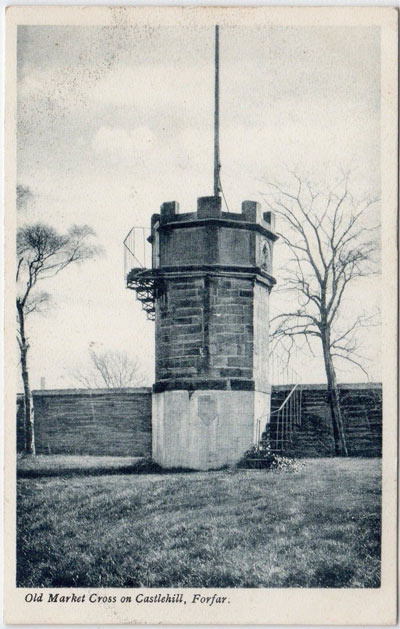

The Forfar tollbooth doesn’t exist anymore – the dilapidated medieval tolbooth was replaced with the Town and Country Hall. The Market Cross which stood outside the Tollbooth has been moved to Castle Hill. This historic landmark gives no clue to the religious hysteria, suffering and cruelty for which it was the setting almost 400 years ago when this unassuming burgh was the backdrop to the most widespread witch hunt that Scotland ever had. Between 1661 and 1663, 42 suspected witches were imprisoned in the tollbooth, and so offensive were these prisoners to the good people of Forfar that the windows were boarded up to stop the accused witches from shouting down to the public. The individual characters involved in the accusations, trials and resulting executions make a fascinating tale of misfits, persecution, torture and religious hysteria.

The story starts when King James VI, son of the executed Mary, Queen of Scots, married the young Princess Anne of Denmark in 1589. James has been described as “the most learned man who ever occupied a British throne” and his achievements were many. It was James who foresaw the benefit of a political union between the kingdoms of Scotland and England. He spoke passionately of tolerance in an age of great persecution, he wrote eloquently in English, French and Latin and strongly criticised a new practice that was becoming extremely popular with the ruling classes with publication of his work A Counterblast to Tobacco.

However, when King James’ new bride Anne, whom he had married by proxy, was sailing from Scandinavia to join her husband, she was almost killed during a fierce storm. The ship was forced to take shelter to await calmer weather, so James decided to sail to Norway to escort his bride home. They were formally married in Oslo and after a honeymoon, set sail for Scotland again. When yet another raging storm befell the ship, the captain and the king became convinced that dark forces of evil were working against them.

On his return to Scotland, James led an investigation to find those responsible for the acts of “malefice” and uncovered more than 100 “wyches” in North Berwick. It was clear to the king that these witches had deliberately raised the tempest by swinging cats around their heads and throwing them into the sea. The witches were tried and several were executed in a very high-profile and public trial. The king developed an obsession with these evil-doers who sought to destroy him, and in 1597 published his work Daemonologie, a study of witchcraft and devil worship, with clear instructions on how to identify a witch.

This royal endorsement led to Scottish witch hunts which resulted in the trial of many thousands of accused, mainly women, and the execution of more than 1,000 of these unfortunates.

Most accusations of witchcraft resulted from petty disputes between neighbours or when something disastrous happened inexplicably, like the failure of harvest, the inability of a cow to produce milk or a calf, or a sudden death. People were superstitious and fearful and looked for an explanation – for someone to blame. Very often, they did not have to look far.

In the burgh of Forfar, one local woman, Helen Guthrie, was a well known drunkard and troublemaker – a “verrie drunkensome woman.” She had frequent disputes with her neighbours and liked to frighten people with her claims of supernatural powers. Helen told tales of how she had murdered her own infant sister, Margaret, and was by all accounts a loud and disagreeable individual. Helen was accused – along with her coven – of wrecking a ship in Carnoustie harbour and destroying an important bridge at Cortachy by raising supernatural forces and consorting with the devil himself.

While imprisoned in the Forfar tollbooth, Helen claimed she knew of other witches in the town. She pointed her finger at one Jean Thornton, whom Helen claimed was also in league with the devil. Jean had already drawn attention to herself during a dispute with her own son. He had bought a cow from his mother, but Jean was adamant that the animal still belonged to her because he had not paid for it. A family feud developed which Jean decided to resolve in her own memorable way. She ran to her son’s small farm with a noisy group of women and reclaimed the cow from it’s pen. Jean then rode triumphantly home on the back of the poor beast for all to see.

Such a rowdy behaviour was completely unacceptable at a time when the church had a powerful hold over the daily lives of parishioners. The kirk ministers preached the values of respectability, piety, Godliness and modesty, so outlandish behaviour was seen as scandalous and an affront to public morality.

Other local women were accused, tried and executed after confessing to such outrageous acts as dancing with the devil, flying on broomsticks (which was treated with the flesh of dead infants) and causing the deaths of local worthies by the use of spells and incantations. These confessions were of course, extracted under torture and deprivation of sleep, food and light. The inquisitors in Forfar used the branks – an iron band fastened to the cell wall and around the head of the prisoner with a long barb into their mouth preventing the prisoner from eating, drinking, sleeping or resting, and causing constant agony.

Helen Guthrie, however seemed to delight in feeding her accusers with outlandish tales of her adventures with the devil himself, and was eager to provide names of locals who were also witches. Of the 40 “Forfar witches,” 30 were personally accused by Helen Guthrie. She told of midnight gatherings in the Forfar churchyard or by the loch where she and her fellow coven members would dance with the devil and plot acts of evil.

They desecrated the grave of an unbaptised infant, cooking the remains in a pie. Present at this gathering, claimed Helen, was Isobel Shyrie. The local baillie had recently paid an official visit to Isobel’s home to remove property in place of debt she owed. Soon afterward, he dropped dead, casting suspicion on Isobel. Helen’s affirmation that Isobel had indeed caused the death of this good man led to the latter’s imprisonment in the Forfar tollbooth. There, under toture, she confessed to poisoning the deceased with a potion of “two toad’s heads, a man’s skull and dead man’s flesh which had been perfumed by the Devil.”

In September 1661, she was tried in the tollbooth which was her prison, her jury consisting of five local landowners. They found her guilty of the “abominable cryme of witchcraft,” and the expert services of Donald the executioner from nearby Montrose were employed for the princely sum of 1 pound and 4 shillings to carry out her penalty. Donald strangled Isobel with a rope which had cost 12 shillings and 6 pennies, then she was burned in a barrel which was purchased for the occasion for 16 shillings.

Elspeth Alexander and Janet Stout were two other local women named by Isobel as members of the coven, with both making their confessions to witchcraft the very day after Isobel. They admitted to being part of the group that had destroyed Cortachy bridge and sunk ships by supernatural means. They told of renouncing their Christian baptisms and entering a pact with the devil, all sure signs of being a witch according to King James’ Daemonologie.

Elspeth Alexander was strangled and burned in January 1662 and we assume the same fate for Janet.

John Tailyour was one of the few men accused of witchcraft; he, too, was named by Helen Guthrie. He confessed to the heinous crime of transforming himself into a pig and running amok through his neighbour’s neat cornstalks, causing much damage and havoc. During a meeting with the devil, John had taken the name of Beelzebub as his own.

Helen made many accusations of witches causing harm to the good people of Forfar by using malevolent powers. Those named and tried include Katherine Porter, James Pearson and George Sullie. She prolonged her imprisonment – and her life – by continuing to make her own confessions which included a failed attempt by the devil when he heroically tried to free Helen from the tollbooth, and also by her long list of fellow witches and their crimes.

A serious contender to Helen’s self-claimed title of preeminent witch of Forfar was Isobel Smith who was brought to the attention of the authorities by Helen. Isobel was an admitted adulteress when this was a serious sin against the church and an affront to public decency. Isobel described how she had sold her soul to the devil for the price of 3 half pence per annum. Unlike the coven members who met with their diabolic leader in a group, Isobel met with him one-to-one when he revealed himself to her on a hillside when she was gathering heather.

Isobel and Helen were kindred spirits; they both seemed to attract disagreement and become involved in disputes and feuds. When a farmer’s wife refused to give Isobel milk, she went straight to the cow and helped herself, then took the calf home with her (although she said the animal had followed her). She claimed to have killed another protagonist simply by touching him and putting a hex on yet another enemy, one Janet Mitchell, by holding an image of her. Furthermore, she had caused a fine horse to die after she cursed it when it ate her corn. In those days of hand-to-mouth subsistence, these allegations were very serious because a productive cow or a strong horse was often the only barrier between the family fed or falling into ruin.

During her trial, Helen stated that she could identify another witch simply by looking at her. She was presented with Elspeth Bruce and confirmed that Elspeth was indeed a witch who had caused the death of Lady Isobel Ogilvy. This was obvious, claimed Helen, because Elspeth had been seen dancing around a fire on the night the noblewoman had died. Elspeth was also accused of enjoying a roast goose, a great delicacy, on the very night Cortachy bridge had been destroyed supernaturally by the Forfar Coven. Elspeth was the only one to deny all accusations against her, although she did admit to adultery. In July 1662, Elspeth was tried but no record remains of her fate.

By the end of that year, Helen, was still imprisoned in the tollbooth, eking out a miserable existence by continuing her role as chief witness for the prosecution. By then Helen had become quite a cause célèbre and she was so important a witch that a commissioner traveled from Edinburgh to oversea the proceedings at her trial. On November 14, 1662, the day after her trial, Helen Guthrie was executed and “burnt to ashes.” In addition to the usual fees for the executioner, rope and barrel, an additional 15 shillings was spent on ale for those attending the public burning.

Helen Guthrie was the last witch to be executed in Forfar. After her death several women imprisoned in the tollbooth were released because nobody could be found to speak against them. One of these was Janet, the young daughter of Helen, who was seen as a witch by association. If the mother was a witch, then so was the daughter. Janet was banished from the burgh of Forfar with an exclusion zone of eight miles. Unworthy of marriage, Janet would spend a miserable life as an outcast and a vagrant.

By the time Elizabeth Bruce was released and banished in 1664, public opinion was changing and those in the positions of authority became concerned that due process of law was not being carried out. Many accusations seemed to be personal, petty and vindictive. Fear, superstition and religious intrench began to lessen their hold as new thinking in science, medicine and education shed their light on the population of Scotland.

The witch hunts were over and the burgh of Forfar returned to its business.

Hi, Amanda. The Forfar witches story is very interesting and sad. In fact, I´m now writing a fiction book that include various elements from this events. I´ve read another post, from Chris Longmuir, who gives less details but adds others, like that Helen Guthrie said that “she have been a witch for more than 14 years, after learning her craft from Joannet Galloway in Kirriemuir. Helen claimed that Joannet gave her three bloody papers as proof of her initiation”.

Can you tell me if there´s any kind of official historic record where to get the full details? I´d aprreciate so much your help.

Best regards

Sebastian

The Janet who was banished was Janet Bertie not the daughter of Helen Guthrie ,her name was Janet Howatt and it is not

known what became of her