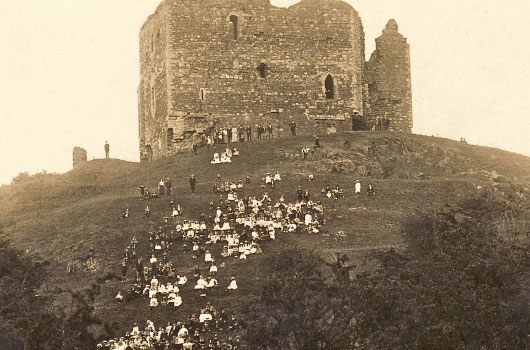

Dundonald Castle is not one of Scotland’s most famous castles, yet it deserves to be. To look at the ruins now, sitting atop a hill in Ayrshire, you wouldn’t realise that it was once a royal residence, and that it played a crucial role in Scotland’s history.

Dundonald has been called the cradle of the Stewarts, that line of ill-fated kings who ruled Scotland and subsequently Great Britain for so long. And it has associations with three other great Scottish families – the Wallaces, the Cathcarts and the Cochranes.

At the foot of the 140 foot high hill is the straggling, typically Lowland village of Dundonald, with its neat cottages and 18th century parish church. The church, it is said, stands on a site which has been sacred for centuries.

To find the beginnings of Dundonald Castle, we must go back 4000 years. The hill on which the castle stands is a “volcanic plug”, the solidified core of an old volcano. It was an ideal site for a settlement, and recent excavations have revealed evidence of people living there in Stone Age times, 2000 years before Christ.

Much later, during the Iron Age, a hill fort was built on the site. This consisted of a stone and turf rampart with a wooden palisade on top which enclosed a large area at the summit of the hill. By about 500 A.D the site had developed into a defensive village of sorts. Timber as well as wattle and daub buildings had no doubt been built within the palisade, and these would have been circular, with conical, thatched roofs.

The village lasted right up until 1000 A.D. Forts of this kind, though defensively strong, had many hazards, not the least of which was fire. And it was a great fire which caused it to be abandoned, after 3000 years of continuous occupation. Archaeological evidence suggests that the heat was so intense that when the wooden palisade caught fire, it melted the stonework on which it was built, creating what historians called a “vitrified fort”.

Dundonald had been within the ancient British kingdom of Strathclyde, the capital of which was at Dumbarton. At about the same time as the fire, this kingdom declined in importance. In 1034 it lost its independence, and was absorbed into Scotland. Possibly for this reason, the fort was never rebuilt. Political power now resided many miles away in Perthshire, and Dundonald became a backwater.

Dundonald means “Donald’s Fort.” No one really knows who this Donald was, although there were at least three kings of Strathclyde by that name in the 10th Century, and one of them may have favoured Dundonald as a royal residence.

Then, in the 12th century, the site’s superb defensive position was once more recognised – this time by a direct ancestor of the Stewarts. It was not a hill fort that was built this time, however, but a wooden castle.

The royal line of Stewart took its name from the fact that at one time they were hereditary high stewards of the Scottish kings. They looked after the royal household, and wielded considerable power.

The first Stewart was Walter FitzAlan, younger son of the Lord of Oswestry in England. The family had its origins in Brittany, and may have entered England as part of the Norman Conquest.

It was Walter who built the wooden castle in about 1136, possibly as his permanent base and home in Scotland. It would have consisted of a timber tower house built on top of a motte, or artificial hill, with, at its feet, the bailey, or fortified area, containing stables, workshops and smithy.

Wooden castles were not uncommon in those days. With the need to establish their supremacy quickly and effectively after the Battle of Hastings, Normans built many castles of wood, only replacing them with stone-built versions when their conquest was complete.

It was the same in Scotland, where Anglo Norman families had also settled. But by the 13th century, stone was being used, and Alexander, a later High Steward, rebuilt Dundonald in stone. By 1300 it was oe of the most impressive castles in the whole of Scotland.

Some historians have claimed that, architecturally and defensively, Dundonald rivalled Edinburgh and Stirling. It contained a stone curtain wall, punctuated by massive towers, a central keep, and an impregnable twin-towered gate-house. The bailey had gone, replaced by the ancestor of the modern village of Dundonald. At one end of the main street would have been the medieval church, standing on the site of the present one, and at the opposite end the castle.

During the Wars of Independence, the castle was all but destroyed. The ruins brooded over the village until the arrival of another High Steward.

But this was no ordinary steward. By this time the name had been changed to Stewart, and the man who rebuilt the ruins was Robert, more famously known as Robert II, King of Scotland.

His mother was Marjorie, daughter of Robert the Bruce, his father was Walter 6th High Steward of Scotland. Robert II was the first Stewart king, and he may have rebuilt Dundonald to mark his accession to the throne in 1371.

The castle he built, however, was simpler than the one built by his ancestor. It consisted of a barmkin, or outer courtyard, surrounded by a high wall, with a great fortified tower inside.

At that time, kings had more than one royal residence, and spent a good part of the year doing the rounds of the kingdom. But Dundonald was certainly Robert’s favourite, and he returned there again and again.

The scene when Robert II approached the castle for one of his stays must have been impressive. The long procession of dignitaries, soldiers, countries and servants would have snaked across the Ayrshire plain, and lookouts would have been posted on the tower roof to watch for its approach through the trees that blanketed the landscape.

Prominent in the procession would have been the dignified progress of the Royal Bed, which accompanied the king everywhere. There would also have been chests of fine clothes, barrels of wine and beer, musicians, scribes and secretaries.

Fine horses for the king’s hunt – a favourite sport – would also have been part of the procession, as would great chests of documents for the governance of the country. The stately wagon containing the king and queen would have been in the middle of all of this, curtained off so the riffraff couldn’t see them.

For the first time in weeks, the castle would have been cleaned out. The privies and stables would have been emptied, and fresh straw strewn on the floors of the great hall. Colourful banners would have been hung from the tower and barmkin walls, and flags and pennants would have fluttered in the breeze.

The people of the village below would have been harried from their homes to line the street and cheer the royal progress. A kingly hand may have strayed out from between the curtains on the royal wagon to acknowledge the cheers. If it had been raining, even the street itself would have had straw thrown on it to ease the royal progress through the mud.

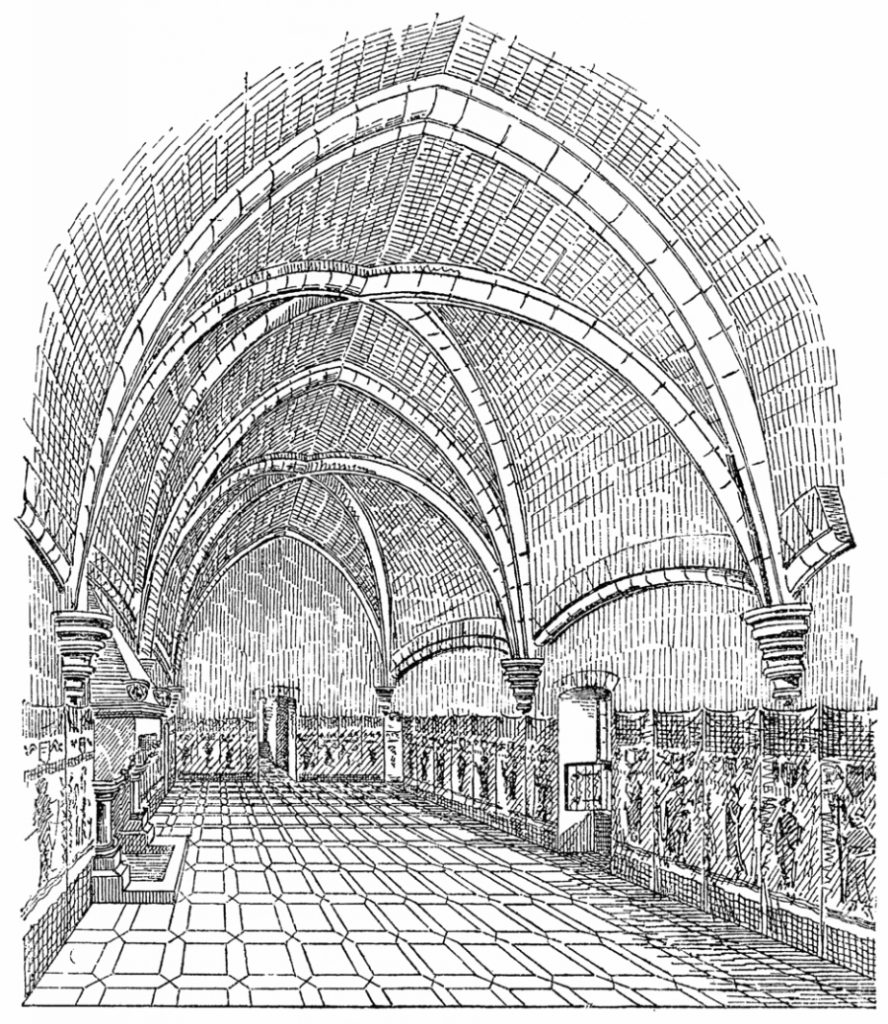

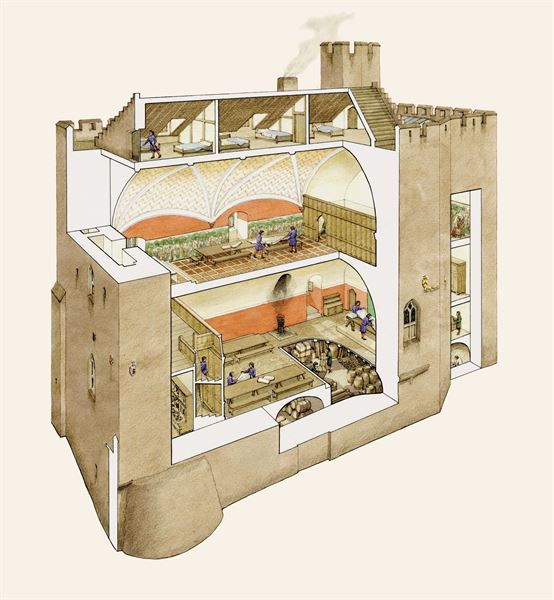

The main tower of Dundonald Castle was typical of its time. At the base was a huge barrel-vaulted hall taking up the whole area of the castle. This was divided by timber flooring into three stories. The bottom floor was used as a storage area and kitchen, and as a place for the servants to sleep. Above this was the laigh hall, the main public area of the castle. Here great banquets would be held and audiences with the king granted. At one end, a wooden screen separated the main body of the hall from the service area, with its staircase down to the kitchens and its latrines. Above the screen was a minstrels’ gallery.

At the opposite end, in a corner of the building, was the spiral staircase which the public used. There was also the king’s seat on a raised dais, from which, when a baron’s court was in progress, he dispensed justice. This was also where the high table was situated during feasting, lit by two large windows on either side.

It looks a chill, bleak chamber today, but when the king was in residence, braziers would have burned brightly, giving plenty of heat and making the air hazy with smoke. Tapestries and bright banners would have hung from the walls, keeping out draughts and adding a splash of colour.

The top story contained the great hall, the king’s private chamber. It was rib-vaulted, and ran the full length of the castle. Here the king and queen could relax, and entertain favourite courtiers. It was also the royal couple’s bedchamber – great pulleys must have been used to haul the royal bed, in several pieces, up the outside of the building and in through one of the windows.

An area would have been screened off to accommodate the royal bed, though at a later dantean extension was built onto the south side as a separate bedchamber. On the west wall was an open fireplace, which no doubt burned logs from the surrounding forests and coal mined in the Ayrshire mines, most of which were owned by the monasteries.

It was within the great hall,in 1390, that Robert II died. He was 75 years old – older than any other Scottish king up until then. An old poem states: “At Dowdownald in his countrie, of a shorte sickness thare deyed he.” The reference to “his countrie” suggests that Robert did indeed have a love for this part of Ayrshire. He was subsequently interred at Scone Abbey in Perthshire.

He was succeeded by his eldest son John, Earl of Carrick, who took the name Robert III, due no doubt to the unfortunate associations of his real name with John Balliol.

Through Robert III often stayed at Dundonald Castle, he didn’t have the love for it that his father did. He died in 1405, not at Dundonald as some people claim, but in Rothesay Castle on the Isle of Bute.

Dundonald Castle remained a royal residence, however. All the Stewart kings up until James V stayed there at some time or other. In about 1482, James III granted the use of the Castle and its lands to the Cathcarts, a famous lowland family. Then, in 1527, it was sold by James V to the Wallaces of Craigie Castle – a family closely related to Sir William Wallace.

By the Reformation, part of the Castle had become a prison, and the actual prison cell beneath the new extension built for Robert II can still be seen.

The Wallaces supported the Covenanters in the 17th century and fell out of favour with the Stewart monarchy in London. They therefore sold the Castle to the Cochranes. The place by this time was falling into disrepair, and the Cochranes built a new residence nearby, using some of the castle’s stonework to do so. Their new home was Auchans House, later home to Susanna, Dowager Countess of Eglington, who died in 1780.

The Cochranes were raised to the peerage by Charles II. They took the title “Earls of Dundonald,” and indeed the first Earl is reputed to be buried beneath where the present Dundonald parish church now stands.

Perhaps the most famous member of the family was Thomas, the 10th Earl. He was an admiral in the navy during The Napoleonic Wars, after falling out of favour with the Admiralty in London, took himself off to Chile, Peru and Brail, where he served in each of those countries’ navies. It was Thomas’s grandson who raised the Siege of Lady-smith during the Boer Wars in South Africa.

From the early 1700s onwards, the Castle gradually became a ruin. When Samuel Johnson and his biographer Boswell visited in 1773, Samuel stood amid the ruins and laughed at the humble residence of “King Bob.”

In the early 1990s, Historic Scotland decided to stabilise the ruins and open the castle to the public. It is now looked after by an organisation called “The Friends of Dundonald Castle.”

Once more you can clamber to the top of the castle, by means of a metal stairway and not the original circular staircase, and stand in the room – now open to the elements – where Robert II died.

Only scant evidence of the original stone castle built by Walter FitsAlan remains. The stump of a tower and the great gatehouse can be seen, plus a well which at one time was sunk within it. The rest, however, is the stonework of the royal castle built by Robert II.

There are medieval masons’ marks to be seen on the stonework, and embedded in the west wall are small coats of arms, placed there when Robert II had the place rebuilt.

Dundonald is an important part of Scotland’s history, now placed firmly on the Ayrshire tourist trail. Those interested in Scottish history – and the history of the Stewarts in particular – should pay a visit any time they’re in Ayrshire.

I have James I,II, III and IV, Robert I,II,III, listed a few different times in my family tree.. My Connection is from Jane Dunlop who Married John Dunbar Howe 5x great grandparents. A dunlop married a Hamilton. Sorry can’t think of the name of hand.