After the ’45 uprising, Scotland was needed to be ‘brought to heel’, and the army showed little mercy. Jacobites were rounded up, imprisoned or executed. Hanoverian forces were held back by poor mapping, a great Military Survey of Scotland, “undertaken by order of William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland”, was commissioned. William Roy, a factor’s son from Lanarkshire, 19 at the time of Charles Edward Stuart’s expedition, was put in charge of the small group of men who were to undertake the physically exhausting, technically demanding work of surveying Scotland, under the supervision of the Board of Ordnance. (view full map here >) It is really worth taking a look at this map, the artwork is incredible.

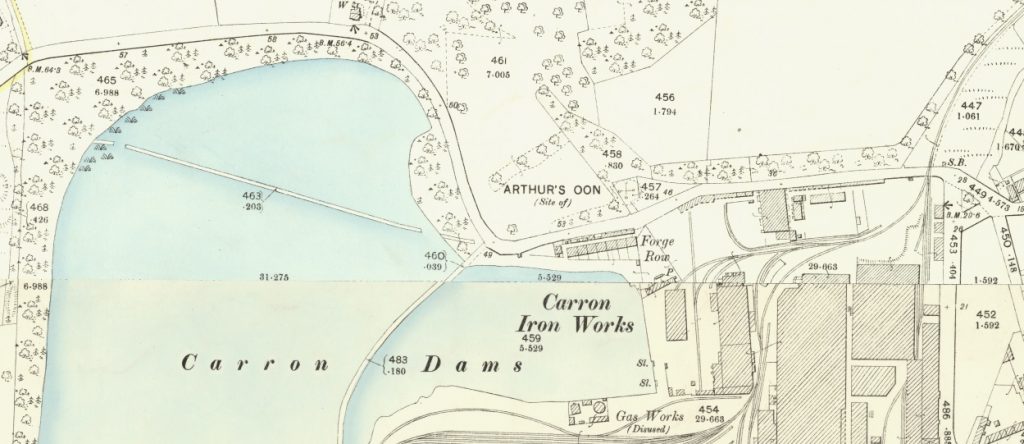

On Roy’s map of the Antoine wall, just north of Falkirk on the banks of the river Carron you can make out the words ‘Here stood Arthur’s Oon’. Oon or O’on means Oven. This is not a place many people have heard of but was one of the most important monuments not just in Scotland but in the whole of the British Isles.

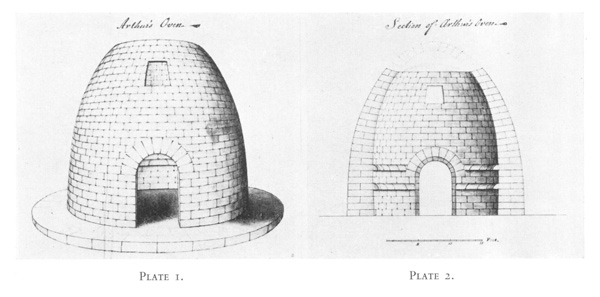

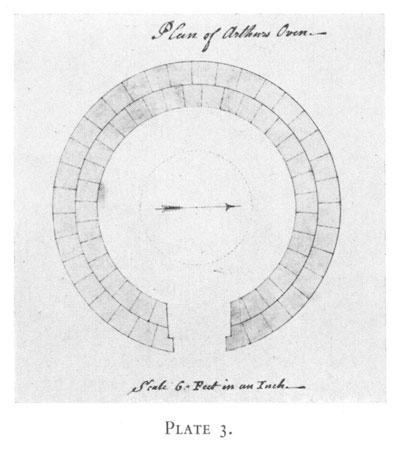

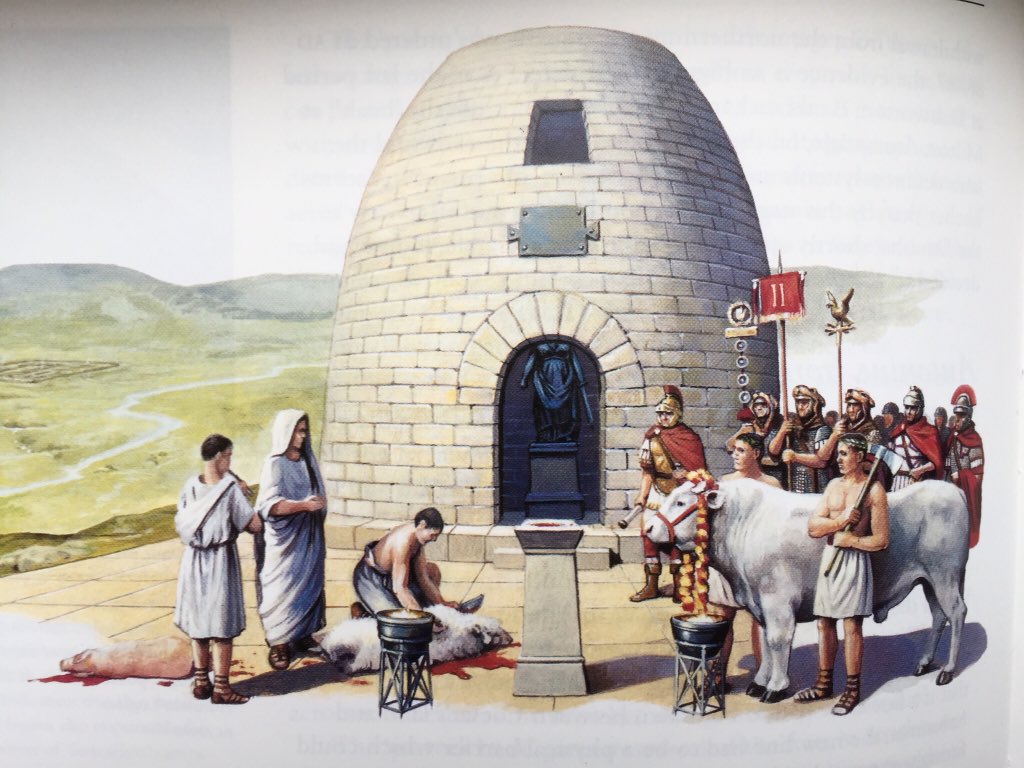

Arthur’s O’on was a beehive-shaped stone building which stood on the northern bank of the river Carron, it’s purpose is not known and there are a few different theories. The appearance of the O’on is something there is general agreement on; it was a domed circular building built of dressed freestone which were not mortised into each other. The O’on had a circular paved floor the circumference of which was 61 feet. The building’s height was 22 feet. The thickness of the wall was 4ft 6 inches. The door would have been made of iron. Over the doorway there would have been carvings. Inside a huge stone stood possibly an altar or the base of a bronze statue.

It is thought that this ‘stone house’ was the reason for the name of the nearby ‘Stenhousemuir’. Stenhousemuir was originally called the village of Stonehouse, as it is marked on Roy’s map. (Thus Arthur’s O’on has the distinction of being the only Romano-British monument to have a football team named after it.)

Blair Castle Discovery

In 1969 Miss Catherine Cruft discovered an unpublished first-hand description in the form of a manuscript at Blair Castle.

The Blair Castle manuscript is in the form of a booklet 9.5 inches square made up of eight pages sewn together, the cover bears the title ‘Arthur’s. Oven’. Inside there are four and a quarter pages of text and three pages of drawings. The manuscript is neither signed nor dated. It is from this that we get some wonderful illustrations of the building:

A photographic copy of the manuscript is held in the National Monuments Record of Scotland.

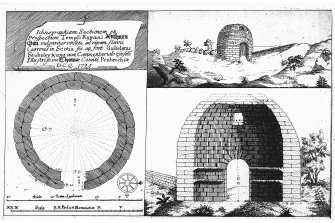

The other illustrations we have are those by Stukeley. The English antiquary William Stukeley published a tract on Arthur’s O’on in 1720.

A Curse upon the Monteiths

The iron door to Arthur’s O’on is said to have had an iron gate, the removal of which by the Monteiths of Cars brought a curse upon the family.

Arthurian Legends

Many legends surround Arthur’s O’on. Due to it’s name it has always been connected to the legend of King Arthur. The early Arthurian names suggest a functional interpretation as an oven or palace of the legendary Arthur. It’s proximity to the village of Camelon, which some identified with Camelot also adds to this theory. One historian, Archie McKerrach claimed that King Arthur held court in Scotland and this could have been the where the story of the round table comes from, he says it was never an actual table but more a round, stone hut.

Controversy surrounds the question of whether Arthur really existed and some historians have argued he is the personification of several people rolled into one. The table was first described in 1155 by Wace. McKerrach says:

“What the text actually says is ‘Arthur built a table rotunda’ – and there is only one building in Britain meriting that description – what is known as Arthur’s O’on, or ‘rotunda’.

“Wace added that ‘all were seated within the circle and no-one was placed outside’ which could hardly mean a circular table but rather a circular building.”

Roman mobile home or store house?

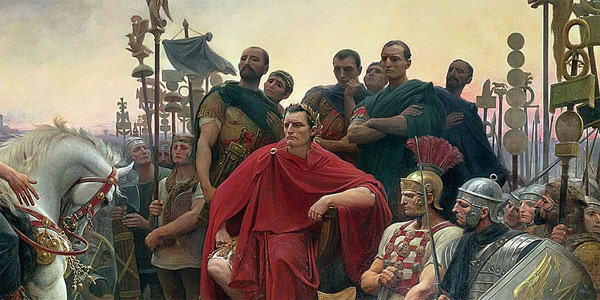

By the time of mapmaker William Roy Arthur’s O’on was confidently ascribed to the Romans, and this has been the main belief since the fourteenth century, when John of Fordun had described it as a ‘rotundam casulam’, a round chamber, ‘columbaris ad instar’, in the form of a dovecote (less convincingly, he argued that it had been built by Julius Caesar either to mark the northernmost boundary of his military endeavours; or else as a kind of mobile home that he had ‘built up again from day to day, whenever he halted, that he might rest therein more safely than in a tent; but that, when he was in a hurry to return to Gaul, he left it behind’.)

William Stukeley published a tract on Arthur’s O’on in 1720, without, let it be said, having made the journey to Scotland to study it in person. Conjecturing that it was a temple ‘dedicated to Romulus the parent and primitive Deity of the Romans’, he compared it lavishly to Rome’s Pantheon, which he had also never seen. (He included just the faintest pre-emptive acknowledgement that ‘some may think we have done the Caledonian Temple too much Honour in drawing such a Parallel’.) Gordon included a description of it in his Itinerarium, arguing that it was ‘not a Roman Temple for publick Worship’ but rather, ‘a Place oe holding the Roman Insignia’, or legionary standards.

The Destruction of Arhur’s O’on

In 1743, however, came disaster. The landowner, Sir Michael Bruce of Stenhouse, decided to build a dam on the Carron, part of the creeping industrialisation of the river that would only a few years later see the opening of the Carron Ironworks. (These are marked on Roy’s map; by 1814 they would be the biggest ironworks in Europe, producing cannon for the Napoleonic wars under contract to Roy’s employer, the Board of Ordenance.) To build his dam, Bruce needed stone: so he simply demolished the Roman building on the riverbank and used its masonry.

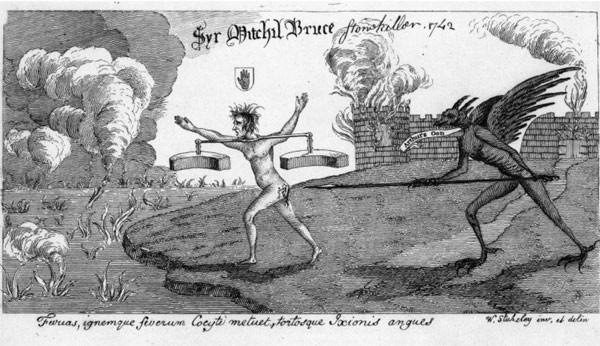

The destruction of what was surely one of Scotland’s most important ancient monuments provoked a furious reaction from antiquaries. Chief among them was Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, a Baron of the Exchequer in Edinburgh. He communicated news of the loss in a despairing letter to his friend and fellow antiquary Roger Gale which he published, he wrote: ‘No other motive induced this Gothic knight to commit such a peice [sic] of barbarity but the procuring of as many stones as he could have raised out of his Quarrys there for five shillings … We all curse him here with Bell, Book and Candle.’ Gale wrote to Clerk: ‘I like well your project of exposing your stupid Goth by publishing a good print of Arthur’s Oven with a short account at the bottom of this curious fabrick when entire, and of its destruction … to be done without mentioning any name but the Brutes.’ Five years later, Clerk was still fulminating in a letter to Stukeley about the ‘barbarous demolition of the ancient Roman temple called Anthers Oven’ and gleefully communicating that ‘some weeks ago the mill and mill dam which had been raised from the stones of Arthur’s Oven, were destroyed by thunder and lightening’. It is almost as if Arthur’s O’on were some kind of ritual sacrifice to the Industrial Revolution. The Carron finally went into receivership in 1982.

Arthur’s O’on had a curious afterlife. Sir John Clerk died in 1755, after composing a set of memoirs, based on his journals, which peter out in 1754 after his taking ill of a flux ‘occasioned by eating too much cabbage broth’. His family had gained much wealth from their coal mines, which enabled Sir John’s successor, Sir James to build a fine new Palladian mansion on the site of the family’s old house at Penicuik. Sir James also erected a handsome stable block. It was a suite of buildings surrounding a quadrangle; on one side, a copy of Arthur’s O’on was built.

The site of Arthur’s O’on is now a housing estate, and no sign or mark tells a passer-by, or even the people who live there, of the former glory that lies beneath their feet. A sad finale indeed!

The following is an engraving marking the demolition of Arthur’s O’on by Sir Michael Bruce Published in the Antiquarian Repertory, 1780.

Sources

- K. A. STEER, MA, PhD MORE LIGHT ON ARTHUR’S O’ON (https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/pdfplus/10.3366/gas.1976.4.4.90)

- Under Another Sky: Journeys in Roman Britain By Charlotte Higgins

Haha, Grew up in Adam Crescent – Arthur’s O’on and had no idea… I’d heard a castle was there, before that a roman Fort, the truth as always is way more interesting..