A 5,000-year-old whalebone figurine, one of the oldest representations of a human form ever found in Britain, has been rediscovered after going missing for more than 150 years. The figurine has been dubbed the “Buddo” of Skara Brae a name taken from an Orcadian word meaning ‘friend’. It was carved from a single piece of whalebone and measures about 3.7 inches (9.5 centimeters) high and 3 inches (7.5 cm) wide. Holes for eyes and a mouth have been cut in the face, and another hole in the body forms a naval or bellybutton.

It was first discovered in the 1860s, but just over 15 years later the figure had completely vanished. It was presumed that it had remained in a collection at Skaill House right until the 1930s. But when that collection was dispersed amongst several museums there was no record of it going anywhere.

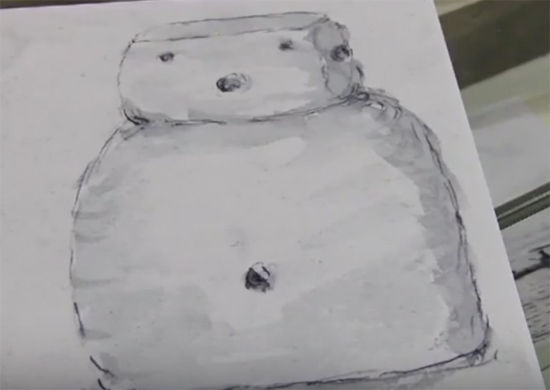

Only a sketch of it remained made by Victorian Antiquarian George Petrie.

That was until British archaeologist David Clark rediscovered it in a box in the archives of the Stromness Museum at Orkney in April. Clarke said that he was reviewing the museum’s stores of artefacts from Skara Brae when he found the Neolithic figurine.

“We were going through boxes quite quickly for me to get a sense of what’s there, and in the last box of the afternoon I opened it up and there he is, just lying there looking at me,” Clarke said. “It was amazing, I was just gobsmacked.”

The figurine was found in a stone bed compartment in a building known as “House 3” at Skara Brae. The site was uncovered in sand dunes by a major storm in the winter of 1850, and it was first excavated by William Watt, the laird of a nearby manor named Skaill House.

Skara Brae is now a UNESCO World Heritage site, and famed for the remarkable preservation of its stone houses, which were built partly underground — possibly to insulate them against the weather, archaeologists have said.

Clarke said the Buddo figurine was described as an “idol” or a “fetish” by the Scottish antiquarian George Petrie, who reviewed the finds from Skara Brae and published a report on the discoveries in 1867. At the time, it was the oldest human figurine found anywhere in Britain.

Archaeologist Hugo Anderson-Whymark, a trustee of the Stromness Museum, was working with Clarke when the figurine was rediscovered.

The Buddo is now on display as the “jewel” of the Stromness Museum collection. A 3D model has also been created and can be viewed online here >

The purpose of the figurine is not yet known, it could have been left on purpose on the floor of the home where it was found when the village was abandoned, perhaps as part of a ritual for departure. Similar deposits of objects were previously found in other Neolithic houses at the site.

Archaeologists think Skara Brae was abandoned by its inhabitants around 2500 B.C., possibly because the local climate had become much colder and wetter at that time.

Clarke said the Buddo seemed to be carved from a whale vertebrae. One of the natural canals of the vertebrae runs through the Buddo from ear to ear, which may have been used to hang it up in some way. Another hole in the bottom of the figurine may have been used to attach separate legs, like a doll, he said.

Antonia Thomas, an archaeologist from the University of York said:

“This rarity of human figures in Neolithic British and Irish art may signify a religious taboo against artistic representations of humans and animals, said Antonia Thomas, an archaeologist from the University of York, in the United Kingdom.

“What is extraordinary about the Neolithic of Britain and Ireland as a whole is the almost complete lack of any representations of humans or animals, or indeed anything from the living natural world,”

“In continental Europe, you see animals and people represented, but in Britain and Ireland you don’t at all — the art work is all geometric and abstract, and you don’t really find these figurines, they are exceptionally rare,” she said. “So, it has led some people to think there may have been some sort of taboo on representing living forms, rather similar to the Islamic taboo, and that’s quite an interesting line of inquiry.”

Thomas said many of the extraordinary finds from Skara Brae — including bone and stone necklaces, pendants, beads, and pins for hair and clothing — gave archaeologists insight into the personal lives of the Neolithic people who lived there.

“We very rarely get a glimpse into the more personal aspects of people in the Neolithic. To have things like this jewelry and now this figurine, you are really starting to get a sense of identity, and connecting more with people,” Thomas said.

Several stone and whalebone pots found at Skara Brae contained pigments that were probably used on the walls of houses, to decorate pottery, and possibly to decorate people’s bodies, she added.

“We’re really starting to get a sense of how people lived, how they liked to adorn themselves and to think about themselves,” Thomas said.