It’s interesting to learn that until 1996 the bagpipes were classified as a weapon of war. This does not simply mean an instrument played in battle, or a tool used to direct troops, it actually means a physical weapon, like a sword or a musket. The origins of this take us all the way back to the Battle of Culloden and a piper named James Reid.

It’s interesting to learn that until 1996 the bagpipes were classified as a weapon of war. This does not simply mean an instrument played in battle, or a tool used to direct troops, it actually means a physical weapon, like a sword or a musket. The origins of this take us all the way back to the Battle of Culloden and a piper named James Reid.

James Reid was one of several pipers who played at the Battle of Culloden. He was captured along with 558 men by Cumberland’s troops and taken to England. There James was put on trial and accused of high treason against the English Crown. Piper Reid claimed that he was innocent because he did not have a gun or a sword. He said that the only thing he did that day on the battlefield was play the bagpipe.

After some deliberation the judges had a different opinion on the matter. They said that a highland regiment never marched to war without a piper at its head. Therefore, in the eyes of the law, the bagpipe was an instrument of war. James Reid was condemned and subsequently hanged then drawn and quartered.

The decision of those judges has echoed down through the generations. It was the first recorded occasion that a musical instrument was officially declared a weapon of war. For hundreds of years and many conflicts to come the bagpipes, when listed among the items captured in combat, was counted among rifles, sabres, and munitions. It is interesting to note that bugles and drums were recorded as musical instruments, where the bagpipe ranked among the lists of weapons. This continued through the Great War. Perhaps a fitting place for the pipes, but a tragic legacy for the piper James Reid who played at the last bloody battle of the Jacobites on Culloden Moor.

In 1996, after some disputes with authorities, a man known as Mr Brooks was taken to court for playing the pipes on Hamstead Heath, an act forbidden under a Victorian by-law stating the playing of any musical instrument is banned. Mr Brooks plead not guilty by, claiming the pipes are not a musical instrument, but instead a weapon of war , citing the case of James Reid as a precedent. The unanimous verdict was that the pipes are first and foremost musical instruments returning them from a weapon of war to their rightful place as a musical instrument.

Famous Pipers

Bill Millin

William “Bill” Millin, commonly known as Piper Bill, was the personal piper to Simon Fraser, 15th Lord Lovat, commander of 1st Special Service Brigade. Millin is best remembered for playing the pipes whilst under fire during the D-Day landing in Normandy.

William “Bill” Millin, commonly known as Piper Bill, was the personal piper to Simon Fraser, 15th Lord Lovat, commander of 1st Special Service Brigade. Millin is best remembered for playing the pipes whilst under fire during the D-Day landing in Normandy.

Millin was born in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada on 14 July 1922. His father, who was a native Scot, moved the family back to Glasgow when he was three. He joined the Territorial Army in Fort William and played in the pipe bands of the Highland Light Infantry and the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders before volunteering as a commando and training with Lovat at Achnacarry, near Fort William in Scotland. Lovat had appointed Millin as his personal piper during this commando training.

Pipers have traditionally been used in battle by Scottish and Irish soldiers. However, the use of bagpipes was restricted to rear areas by the time of the Second World War by the British Army. Lovat, nevertheless, ignored these orders when making their landing at Sword Beach on D-day and ordered Millin, then aged 21, to play. When Private Millin demurred, citing the regulations, he recalled later, Lord Lovat replied: “Ah, but that’s the English War Office. You and I are both Scottish, and that doesn’t apply.” He played “Hielan’ Laddie” and “The Road to the Isles” as his comrades fell around him on Sword Beach.

Millin was the only man during the landing who wore a kilt, the same Cameron tartan kilt his father had worn in Flanders during World War I, and he was armed only with his pipes and the sgian-dubh, sheathed inside his kilt-hose on the right side. In keeping with Scottish tradition, he wore no underwear beneath the kilt. He later told author Peter Caddick-Adams that the coldness of the water took his breath away. Millin states that he later talked to captured German snipers who claimed they did not shoot at him because they thought he was crazy.

Lovat and Millin advanced from Sword Beach to Pegasus Bridge, which had been defiantly defended by men of the 2nd Bn the Ox & Bucks Light Infantry (6th Airborne Division) who had landed in the early hours by glider. To the sound of Millin’s bagpipes, the commandos marched across Pegasus Bridge. During the march, twelve men died, most shot through their berets. Later detachments of the commandos rushed across in small groups with helmets on. Millin’s D-Day bagpipes were later donated to the now Pegasus Bridge Museum.

Millin saw further action with the 1st SSB in the Netherlands and Germany before being demobbed (demobilised) in 1946 and going to work on Lord Lovat’s highland estate. In the 1950s he became a registered psychiatric nurse in Glasgow, moving south to a hospital in Devon in the late ’60s until he retired in the Devon town of Dawlish in 1988. He made regular trips back to Normandy for commemoration ceremonies. France awarded him a Croix d’Honneur award for gallantry in June 2009.

Millin saw further action with the 1st SSB in the Netherlands and Germany before being demobbed (demobilised) in 1946 and going to work on Lord Lovat’s highland estate. In the 1950s he became a registered psychiatric nurse in Glasgow, moving south to a hospital in Devon in the late ’60s until he retired in the Devon town of Dawlish in 1988. He made regular trips back to Normandy for commemoration ceremonies. France awarded him a Croix d’Honneur award for gallantry in June 2009.

Millin, who suffered a stroke in 2003, died in hospital in Torbay on 17 August 2010, aged 88. His wife Margaret, from Edinburgh, died in 2000. He was survived by their son John.

With the help of son John Millin and the Dawlish Royal British Legion, a bronze life-size statue of Piper Bill Millin was unveiled on 8 June 2013 at Colleville-Montgomery, near Sword Beach, in France, which can be seen on the left.

Did you know?

Bagpipes were commonly used during World War I to lead the men ‘over the top’ of the trenches and into battle. However, unarmed and drawing attention to themselves with their playing, pipers were always an easy target for the enemy. The death rate amongst pipers was extremely high: it is estimated that around 1000 pipers died in World War One.

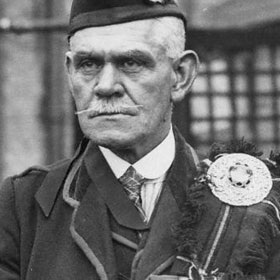

Piper Daniel Laidlaw

Born at Little Swinton, Berwickshire on 26 July 1875, Laidlaw joined the Army in 1896. He served with the Durham Light Infantry in India where he received a certificate for his work during a plague outbreak in Bombay in 1898. In the latter year he was claimed out by his elder brother and transferred as a piper to the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, and in 1912 he transferred to the reserve. In 1915 Laidlaw re-enlisted in The King’s Own Scottish Borderers.

Born at Little Swinton, Berwickshire on 26 July 1875, Laidlaw joined the Army in 1896. He served with the Durham Light Infantry in India where he received a certificate for his work during a plague outbreak in Bombay in 1898. In the latter year he was claimed out by his elder brother and transferred as a piper to the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, and in 1912 he transferred to the reserve. In 1915 Laidlaw re-enlisted in The King’s Own Scottish Borderers.

On September 25th 1915 the company were preparing to ‘go over the top’. Under heavy fire and suffering from a gas attack, the company’s morale was at rock bottom. The commanding officer ordered Laidlaw to start playing, to pull the shaken men together ready for the assault.

Immediately the piper mounted the parapet and began marching up and down the length of the trench. Oblivious to the danger, he played, “All the Blue Bonnets Over the Border.” The effect on the men was almost instant and they swarmed over the top into battle. Laidlaw continued piping until he got near the German lines when he was wounded. As well as being awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces, Laidlaw also received the French Criox de Guerre in recognition of his bravery.

Did you know?

The original purpose of the pipes in battle was to signal tactical movements to the troops, in the same way as a bugle was used in the cavalry to relay orders from officers to soldiers during battle.

Fighting Jack Churchill

Fighting Jack Churchill or Mad Jack, was a British soldier who fought throughout the Second World War armed with a longbow, bagpipes, and a basket-hilted Scottish broadsword (sometimes incorrectly called a Claymore). He is known for the motto “any officer who goes into action without his sword is improperly dressed.”

Fighting Jack Churchill or Mad Jack, was a British soldier who fought throughout the Second World War armed with a longbow, bagpipes, and a basket-hilted Scottish broadsword (sometimes incorrectly called a Claymore). He is known for the motto “any officer who goes into action without his sword is improperly dressed.”

Churchill was born in Ceylon, Sri Lanka but soon after Churchill’s birth, the family returned to Surrey, England. John ‘Jack’ Churchill was educated at King William’s College on the Isle of Man. Churchill graduated from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, in 1926 and served in Burma with the Manchester Regiment. He left the Military in 1936 only to re-enlist when Germany invaded Poland in 1939.

Churchill had an extensive list of herioc and ‘mad’ exploits throughout his life, so let’s take a look at a few of what can be described as the most epic.

As part of the British Expeditionary Force to France, in May 1940 Churchill and his unit, the Manchester Regiment, ambushed a German patrol near L’Épinette, France. Churchill gave the signal to attack by cutting down the enemy Feldwebel (sergeant) with a barbed arrow, becoming the only British soldier known to have felled an enemy with a longbow in WWII.

Jack Churchill was second in command of No. 3 Commando in Operation Archery, a raid on the German garrison at Vågsøy, Norway on 27 December 1941. As the ramps fell on the first landing craft, Churchill leapt forward from his position playing “March of the Cameron Men” on his bagpipes, before throwing a grenade and running into battle in the bay. For his actions at Dunkirk and Vågsøy, Churchill received the Military Cross and Bar.

In 1944 he led the Commandos in Yugoslavia, where they supported Josip Broz Tito’s Partisans from the Adriatic island of Vis. In May he was ordered to raid the German held island of Brač. The landing was unopposed but on seeing the eyries from which they later encountered German fire, the Partisans decided to defer the attack until the following day. Churchill’s bagpipes signalled the remaining Commandos to battle. After being strafed by an RAF Spitfire, Churchill decided to withdraw for the night and to re-launch the attack the next day.

The following morning, one flanking attack was launched by 43 Commando with Churchill leading the elements from 40 Commando. The Partisans remained at the landing area; only Churchill and six others managed to reach the objective. A mortar shell killed or wounded everyone but Churchill, who was playing “Will Ye No Come Back Again?” on his pipes as the Germans advanced. He was knocked unconscious by grenades and captured.

He was flown to Berlin for interrogation and then transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Churchill tunnelled out of the camp with an RAF officer, but was recaptured and transferred to a PoW camp in Austria. When the floodlights failed one night he escaped and, living on stolen vegetables, walked across the Alps near the Brenner Pass. He then made contact with an American reconnaissance column in the Po Valley.

Churchill had always wanted to serve with a Scottish regiment, and so transferred to the Seaforth Highlanders, becoming a company commander where he remained until he retired in 1959.

Thanks for sharing! Very interesting, did not know. Would like on occasions to download some of your information you sharing on facebook. I try to save the information but never seems to get the pictures with the work saved.

One of my bucket list items is to lead troops into a combat zone with my pipes, playing Grade 1 marches like “The Links of Forth”.

However as time goes on, it will become less and less likely that the Highland Bagpipe will be used for any purpose in Modern Warfare except maybe marching troops across terrain and other such purposes.

The tradition of Piping troops into battle is centuries old. It is a myth that Pipers traditionally carried no arms other than their pipes though. Ipers always were…. Warriors or Caterans of the class of Gentlemen known in Gaelic as Duine Assal.

Olthere are many stories of Pipers such as tye McCrimmons within the Clan system.

You speak of everything except of where the bagpipe as an instrument of war originated. It was with the legion of Julius Caesar where the the sound from the apps one style bagpipe (drones facing down) where used to spook and disperse the horses of the fierce highlanders cavalry both at the Hadrian and Antonine walls, thereby securing a Roman victory and rule over Brittania. Once the highlanders and brittons of that time saw what had happened, they adopted the bagpipe as a weapon of war to march and lead the troops in battle, to psychologically instill fear in the enemy, let them know we do not fear you, were coming and we’re not stopping until we have won.

Nice to read about these famous men who piped during wars. In particular I was pleased to read about Piper Laidlaw from Little Swinton, Berwickshire, Scottish Borders. I have heard about his place of buriel from my family and they have visited his grave. RIP Mr Laidlaw.

My late Scottish father once told me that “A Gentleman never plays the pipes.” After his death, I learned that he could play the pipes quite well.