In 1530 James V, king of Scotland, was a mere lad of seventeen. Freed at last from the clutches of those men who endeavoured to reign in his stead, in his minority, he was determined to prove that he was the real power in Scotland.

One area where allegiance to the clan and its leader came before any deference to royal power was the Scottish Border country. There the clans were a law unto themselves, particularly troublesome and unruly.

Accordingly he moved south from his seat in Edinburgh intent on doling out justice and punishment to those who were of particular notoriety. It is said he had six thousand armed followers.

The history of Johnnie Armstrong of Gilnockie, a power in the Scottish Borders, is well recorded. By subterfuge, some say as the result of a ‘loving letter’ he was encouraged to wait upon the king at Carlenrig, south of the Borders town of Hawick. There James, incensed by the apparent affluence of the fierce Border Reiver and his twenty-four followers, ordered their execution without trial. Johhnie had fallen into a trap from which there was no way out. He pleaded with the rash, impetuous youth of a king but to no avail. He resigned himself to his fate but not before saying in the Border Ballad which tells his story:-

‘To seek hot water beneath cold ice,

Surely it is a great folly-

I have asked grace at a graceless face,

But there is none for my men and me!’

He and twenty-three of his followers were strung up on the spot. The twenty-fourth was burned alive in vengeance for the burning of a poor women and her son in which he was the instigator.

In time, when maturity replaced the rashness and callowness of youth, James would regret his actions at Carlenrig. He lost any allegiance the Armstrongs of Liddesdale had for the Scottish monarchy on that fateful day in July 1530. In 1542 at the rout of the Scottish army by the English at the Battle of Solway Moss, the Armstrongs withheld their support for the Scottish cause, even harassed the losers as the terrified remnants of the Scottish army fled the field of conflict and headed back north.

James died shortly afterwards. He was about thirty years old.

Before he arrived in Carlenrig in July 1530, James V was determined to mete out the royal justice against two other Border Reivers of particular renown. One was Adam Scott of Tushielaw, known as the ‘King of Thieves’. Not only did he reive both far and wide; he was feared for the way in which he summarily despatched his adversaries. He strung them up from the trees which surrounded his tower at Tushielaw.

He was soon apprehended by the army of James V, and, it is said, hanged from the very trees from which had swung in their death throes many of the Reivers who had contested his bloody and audacious raids.

The other Border Reiver who was the subject of James’ ferocity was William Cockburne of Henderland (near St. Mary’s Loch). It is said he was hanged over the doorway of his Tower there.

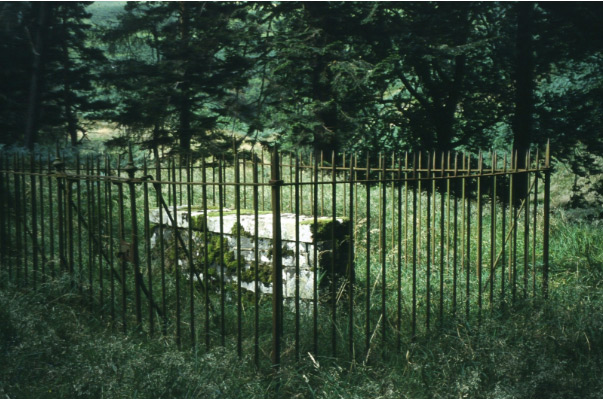

Sir Walter Scott tells us in the ‘Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border’ that ‘in a deserted burial place, which once surrounded the chapel of the castle (the Tower of Henderland), the monument of Cockburne and his lady are still shown. It is a large stone broken in three parts; but some armorial bearings may yet be seen and the following inscription is still legible, though defaced:-

HERE LYES PERYS OF COKBURNE AND HIS WYFE MARJORY.

The table-topped grave can still be seen on a little knoll of a hill in what was the churchyard of the Tower.

Following the deaths of Johnnie Armstrong and his followers emotions ran high and truth ran second best to fact; an approach handed down to the writers of Scottish Border history of the nineteenth century, including the rightly well-respected Sir Walter.

Perys Cokburne was not the William Cockburne who suffered at the hands of James V.

Neither Adam Scott ‘King of Thieves’ nor William Cockburne were summarily despatched within the confines of their own Towers. Rather they were taken to Edinburgh, tried and beheaded.

Robert Pitcairn (1797 – 1855) compiled the documents which recorded the fate of the Border Reivers who were tried and executed. The compilation is known as ‘Pitcairn’s Criminal Trials’.

For 1530 he records the following:-

William Cokburne of Henderland, Convicted (in presence of the King) of High Treason committed by him, in bringing Alexander Forester and his son, Englishmen, to the plundering od Archibald Someruile: And for treasonably bringing certain Englishmen to the lands of Glenquhome: And for common Theft, common Reset of Theft, outputting and inputting thereof – SENTENCE. For which causes and crimes he has forfeited his life, lands, and goods, moveable and immoveable; which shall be escheated to the King.- BEHEADED.

ADAM SCOTT of Tuschelaw, convicted of art and part of theftuously taking blackmail from the time of his entry within the castle of Edinburgh, in ward, of John Browne in Hopprow; and of art and part of theftuously taking blackmail of Andrew Thorbrand and William his brother: and of theftuously taking blackmail from the poor tenants of Hopcailzow: and of theftuously taking blackmail from the tenants of Eschescheill: BEHEADED.

Cockburne, it would seem, was convicted for his alliance with Englishmen which, under the Border Law, was treason, Scott for blackmail which was probably the least of his crimes.

And what of the Border Widow?

One of the most evocative of the Border Ballads is that of the ‘Lament of the Border Widow’. It has always been associated with the death of William Cockeburne following his capture by James V. Although this is historically impossible, it admirably portrays the emotion, the futility, isolation and sorrow which followed many a death in the days of the Reivers.

A BORDER WIDOW’S LAMENT.

My love he built me a bonny bower,

And clad it a’ wi’ lilye flour (all) (flower)

A brawer bower ye ne’er did see,

Than my true love he built for me.

There came a man, by middle day,

He spied his sport and went away;

And brought the king that very night,

Who brake my bower, and slew my knight. (broke)

He slew my knight, to me sae dear; (so)

He slew my knight and poin’d his gear; ( escheated to the king)

My servants all did life for flee,

And left me in extremitie.

I sew’d his sheet, making my mane, (grieving and crying)

I watch’d the corpse myself alane (alone)

I watch’d his body night and day;

No living creature came that way.

I took his body on my back,

And whiles I gaed and whiles I sat; (moved, went)

I digged a grave, and laid him in,

And happ’d him with the sod sae green. (covered) (so)

But think not ye my heart was sair, (sore)

When I laid the moule on his yellow hair? (soil)

O think na ye my heart was wae (weary)

When I turn’d about, away to gae? (go)

Nae living man I’ll love again, (no)

Since that my lovely knight was slain,

Wi’ a lock of his yellow hair,

I’ll chain my heart for evermair.

In the reiving times, the 13th to the 17th centuries, the Scottish English Border was a land in turmoil. Endless confrontation and bloody feud spawned a people who were hard both mentally and physically. The ‘Lament of the Border Widow’ shows another side of the relentless strife which dominated the land of which little is said. Sadness and sorrow followed in its wake.

Thank you… yes, times hard and the hearts of many carried the load…all were just people beside of the road…